The Avant-Garde Concepts of the Late Egyptian Architect Tarek Naga

Having passed away earlier this year, Tarek Naga leaves behind a legacy of unorthodox designs, including the Egyptian Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2000.

In memory of Egyptian architect Tarek Naga, who passed away on November 20th, 2023, we explore his experimental design approaches and theories. The designer and author founded Los Angeles and Cairo-based Naga Studio Architecture in 1991, and his work has been internationally recognised and published across the world.

-87046565-658b-45e9-91f5-6bfbd6488d2e.jpeg)

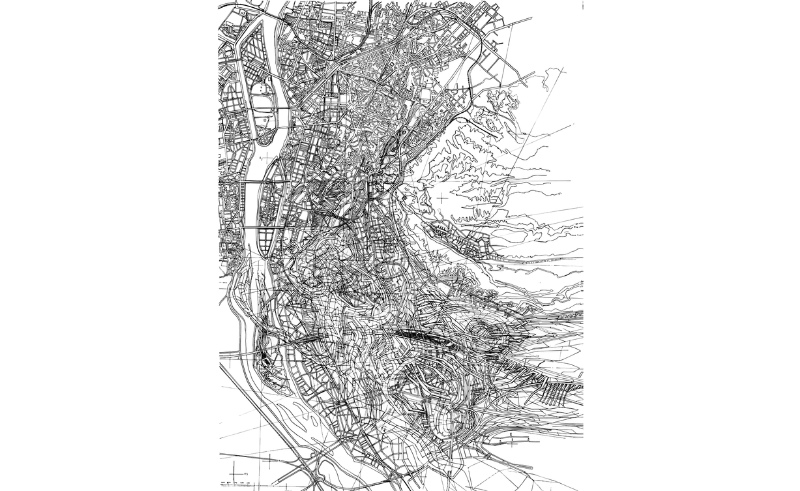

Naga’s projects cover a wide range of scope and complexity with emphasis on public installations and civic projects, including the master planning for the Memphis Necropolis World Heritage Site and Giza Pyramids Plateau. He also worked on the Egypt Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2000, and participated in the first ever TEDx talks held in Egypt.

Known for his unapologetic challenging of the status quo and exploration of avant-garde architecture, Naga lectured in several universities and academic institutions around the globe, including Sci Arc, Art Center College of Design, Cal Poly Pomona in the USA and at the German University in Cairo and the American University in Cairo.

Naga was born in 1953 in Cairo and obtained a Bachelor of Architecture from Ain Shams University in 1975 and a master’s from the University of Minnesota in 1982. Initially trained in traditional architectural styles, Naga found them unsatisfactory and wanted to search for a more substantial form of architecture that didn’t merely continue a style.

Embracing computational advances during the late 1990s and early 2000s allowed Naga to bring forth architectural visions that were, frankly, unlike any seen in the conventional scene. With a strong emphasis on science, art and philosophy, Naga desired to create architecture that transcended the traditional evolution of architectural styles.

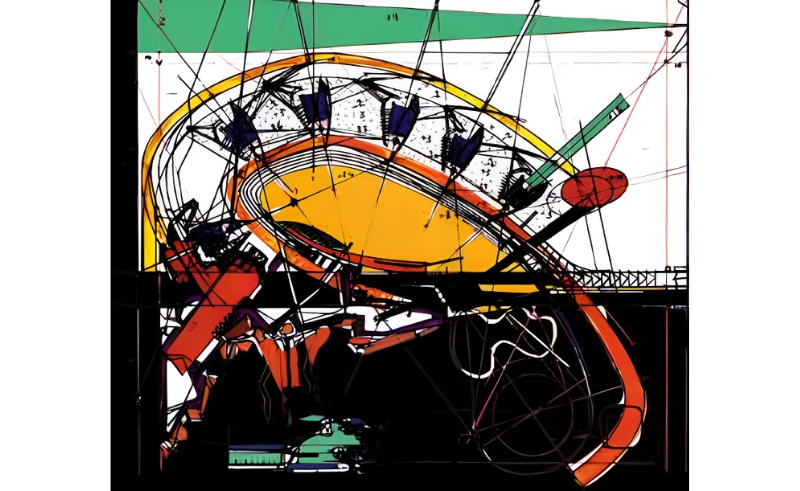

“Without constantly balancing science, art and humanities, you can’t be an architect,” Naga said in his TEDx Cairo talk in 2010 titled ‘Of Phantom Limbs, Sycamores, Towers and the Return of Prodigal Son’. In the talk, Naga shared his fascination with poet Muhammed Afifi Mattar, deriving symbolism from his verses in his design projects, and how this was applied to his work on the Egyptian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2000, which epitomised Naga’s approach to architecture.

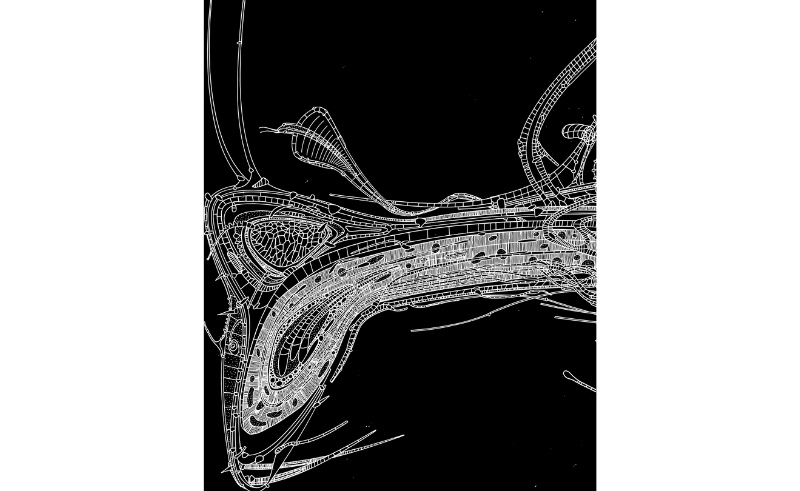

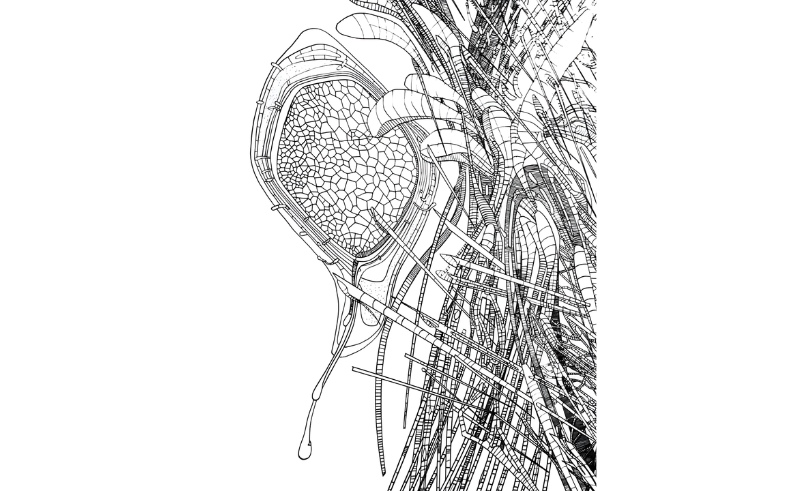

In an attempt to encompass Egypt’s complex history, both the documented and the overlooked, Naga’s design of the Egyptian Pavilion references the Möbius loop, a surface that’s formed by attaching the ends of a strip together with a half-twist, to map a historical timeline that constantly overlaps. Paired with Mattar’s verses on the Egyptian sycamore trees and the use of lead to convey the alchemical process evocative of the ever-changing Egyptian times, the design was brought to life. Naga often blends metaphysics with the physical approaches, viewing Egypt as a collective state of mind rather than just a country.

The 2000 public archive of ArchiLab, an annual architectural conference held in France, offers insight into Naga’s work. Introducing his studio, design approach and featured projects, Naga says in the catalogue briefs, “Architects can no longer afford to lag behind and linger in the post-industrial, post-classical mechanistic models.” The architect derived many of his principles from philosophical literature, referencing the likes of Deleuze and Henri Bergson, arriving at the basic tenets of his experimentation in architecture: ‘The state of becoming and the flow’.

Throughout his career, Naga developed a coordinate system copyrighted as ‘Tetra-Vectors’ which he went on to apply in his computational designs. Without delving too deeply into the mathematics, it basically allowed him to establish a unique relationship between each vector, or point, so that each point in space falls within a particular quadrant and can be activated into motion relative to one another, creating forms that are otherwise too complex to conceive.

The goal, according to Naga, is “architecture that aspires to create spaces which are simultaneously emergent and convergent, imploding and exploding. Spaces that are physically and metaphysically charged with the desire to transform, and transmute themselves.” Here are some examples that demonstrate Naga’s use of Tetra-Vectors…

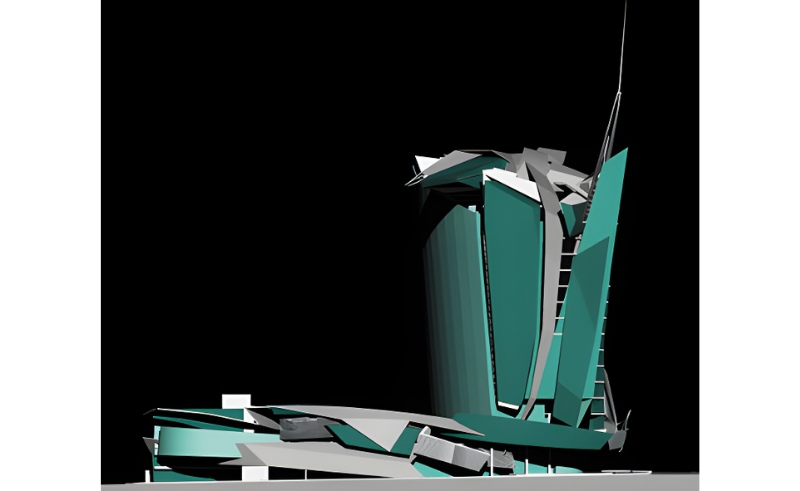

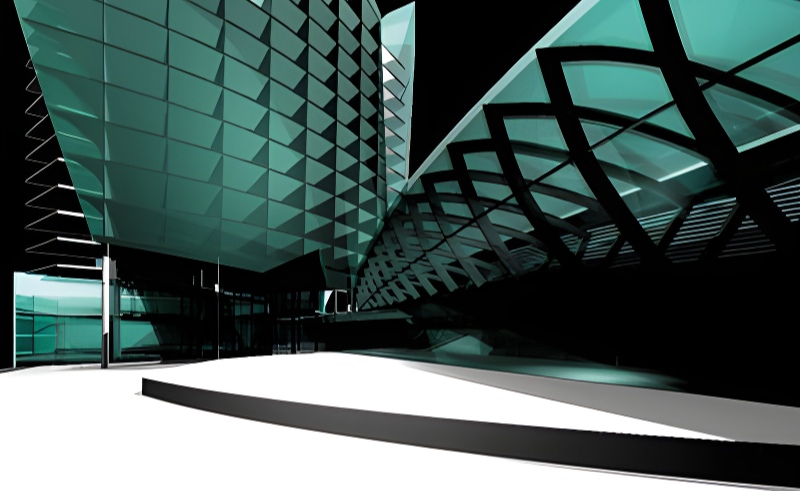

The Red Sea Resort, Hurghada, 1993-94

One of the earliest examples of Naga’s views on ‘architectonics’ and topology are present in The Red Sea Resort. “The overall configuration of the landmass extends out in two armatures embracing the seashore,” Naga explains. “Breaking into smaller fragments, and filtering into the sea, it creates the illusion that the tranquil water had the power to cause such an event.”

At the point where the base breaks apart, the horizontal shards of the hotel and the public functions appear to have spawned more delicate and fragile structures while a sweeping arc of glass emerges from the lagoon. “The interstitial spaces captured between the aquarium’s upward arc movement and the flow of the shifting hotel volumes epitomise a paradox that is inherent in the genius loci of the Red Sea region.”

In Prototype III of the project, which features a cluster of six villas, elements have a tenuous relationship to their base. “The outer shell of each unit is composed of jointed folded plates that allow them to twist, bend or rotate in an assemblage that differs according to their shifting orientations,” Naga describes. “The grouping behaves in a repetitive motion that appears ‘chronophotographic’ in nature’.

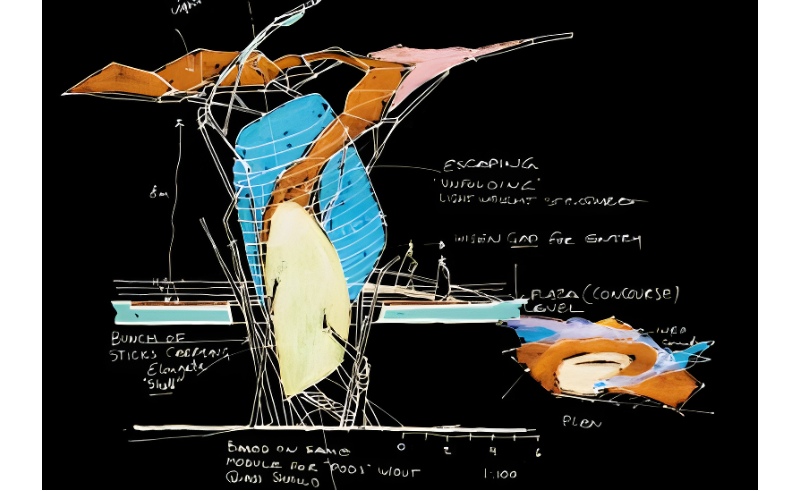

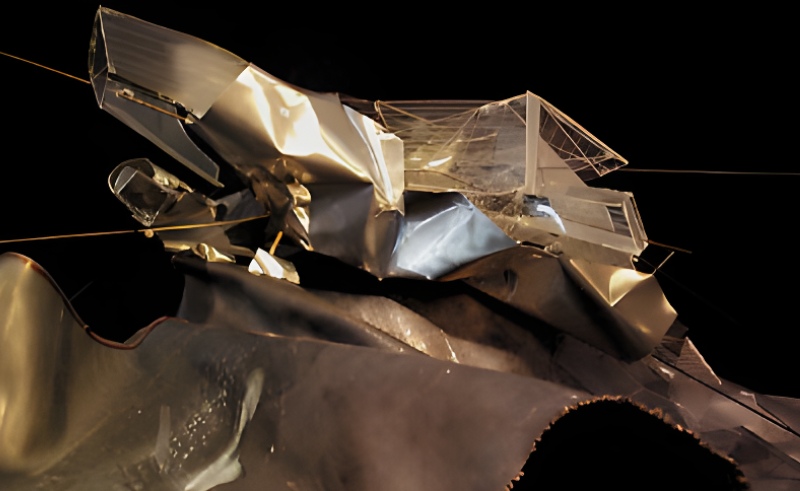

Sharm Safari Gate, Sharm El Sheikh, 1997

The Sinai desert is associated with nomadism and Naga believed that a facility designed for the exploration of such a rich locale has to take its clues from its natural complexity. “The Sinai explorers cross from the realities of this century, into an unknown world of primordial wilderness. This became the basis for the narrative of these five pods that, metaphorically, are themselves wanderers. In search for the mystery of the place they group, evolve and morph into different entities,” he writes.

“One of the pods metamorphosed into an intelligent entity that became their guide,” Naga continues. A membrane that hovered above now shields them. In an act of defiance, the ‘Pod of Flight’ penetrates the shield and nestles above the folded plates. “A place for nomadic explorers is itself conceived by a nomadic myth. The architecture is imbued by the very function it is assumed to perform.”

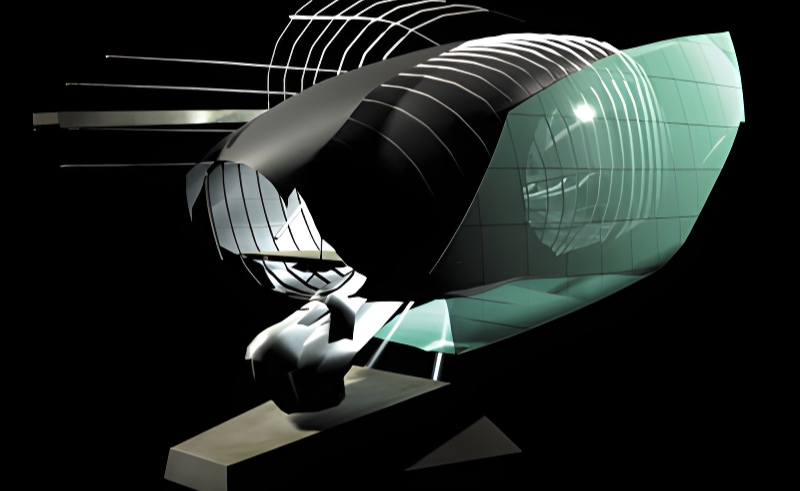

Marina International Hotel, Marina del Rey, Los Angeles, 1998

Intended to function as a dramatic landmark for the marina, the vertical tower consisted of two slabs hinged at the corner, with an edge condition that creates a smooth ‘knife-like’ shard that moves both upward and downward. An elliptical volume floats horizontally over the inner court level, sliding and carving a void into the tower’s base.

“The intersecting forces of both vortices, the vertical and the horizontal, carve out the public restaurant entry. On the narrow edge of the split tower slabs, a folded plate climbs up, wrapping the sides and unfurls at the top creating a roof garden’s shed,” Naga says, describing the feature that overlaps with a suspended bar-in-the-sky twist that cantilevers out.

ESK House, Cairo, Egypt, 2000

Here, Naga dealt with three aspects of the client’s life, which defined the morphologies and spatial behaviour of the house. The client was a filmmaker, satellite engineer and water polo player. Naga translated each one of those aspects into a set of suspensions within the model, each creating their own inspired forms.

The design is a descending arc connecting the sleeping quarters with the living area pointing towards the lower plateau of the land. A vessel membrane contains the house components and is suspended on the hillside to provoke a sense of instability on one side, while it’s cradled by the continuous contours on the other side, evoking a sense of comfort and stability.

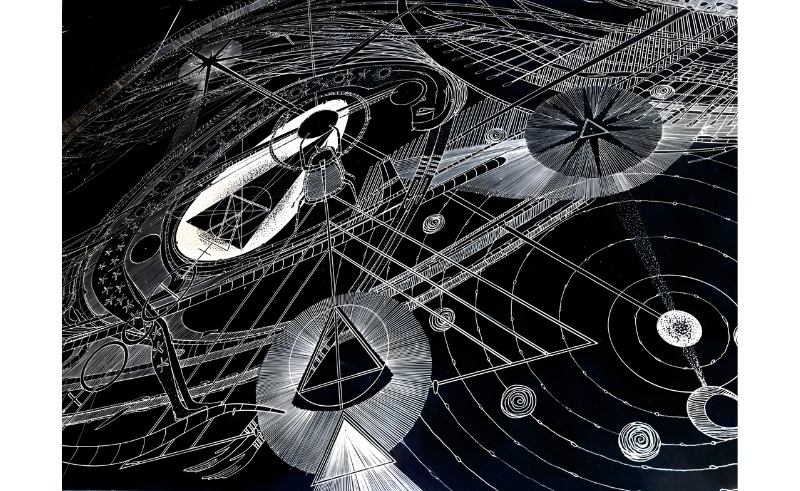

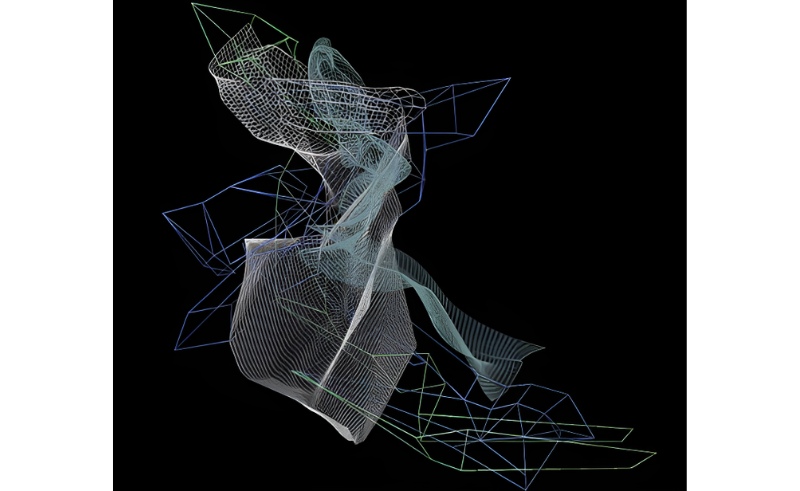

ChaösGnösis, 2010

‘ChaösGnösis’ was a term coined by Naga, referring to the juxtaposition and fusion of ‘the state of chaos’ with ‘the state of gnosis’. This was one of Naga’s more recent works, which he created as an artistic-philosophical project. The project attempts to engage with new horizons of architecture by way of, as you might have guessed, chaos.

“The conventional wisdom and the stereotypical adages of ‘form follows function’ and ‘architecture is frozen music’ all imply an inherent and essential order to architecture,” Naga writes in ‘Complessità e Sostenibilità nel Progetto’, 2013. “The quintessence of architecture, as a human cultural production, is the creation of space and the ordering of space. Architecture’s lofty ideals aspire to crystallise and morph humanity’s inexorable attempts at imitating and taming nature, in making something out of nothing, in reaching a state of order out of disorder.”

Through ChaösGnösis, Naga explores chaos and disorder claiming that chaos isn’t defined by its disorder as by the speed with which every form taking shape in it vanishes. “Conceptualising in architecture, possibly more than the other arts, suffers from the tyranny of opinions - the accepted and acceptable norms and traditions de jour - in a way that can be paralysing to the entire process,” Naga writes. “This explains the characteristic explosive nature of radical thinking. Genuinely new concepts typically come in loud flashes, bursting from under the unbearable heaviness of tyrannical traditional thinking and its appointed custodians.”

To say that Naga was unorthodox or revolutionary would be an understatement. His dive into the conceptual realm of architecture and philosophy allowed him to arrive at a rather perplexing view of architecture as a double-edged sword. On one hand, it preserves humanity’s physical heritage. On the other, it’s the victim of this heritage’s persistence on “lingering in a vacuum of its own making.”

Visionary architects often face fierce resistance as they struggle with the chaotic world of art and architecture. But through this struggle they bring forth visions that are of singular value. This experimental wave that Naga rode was fueled not only by digital advancements but also by his inherent belief that the architecture of the future will bear little resemblance to the architecture of the past. Rest in peace.

Images Credit: Naga Studio Architecture, Archilab 2000 archive, Tarek Naga

- Previous Article rthrtuytyu

- Next Article Ahmed El Awady's 'El Eskandarany' is Coming to Cinemas This January

Related Articles

Trending This Week

SceneNow TV

Events Calendar