Cairo as Protagonist: How Neorealism Cinema Portrays a Fading City

We look back at how the Egyptian Neorealism movement contextualized Cairo in the transformative era of the 1980s.

In Mohamed Khan’s 1984 film Kharag Wa Lam Ya’ud (Missing Person), the opening credits feature the statement, “The characters may be fictional, but trust that the places are real.” This phrase could be seen as emblematic of Khan’s entire generation of filmmakers, who spearheaded what is arguably the most influential cinematic movement in Egyptian cinema. This movement would later be termed “The Neorealism Cinema Movement” by critic and author Samir Farid.

This generation of directors abandoned conventional studio-based filmmaking, choosing instead to delve into the complexities of real-life experiences, locations and stories of Egyptian society. Through their films, they depicted the political, social, economic and cultural dynamics of the time, spearheading a new course for Egyptian cinema that reshaped the film industry and established entirely new standards for filmmaking in Egypt.

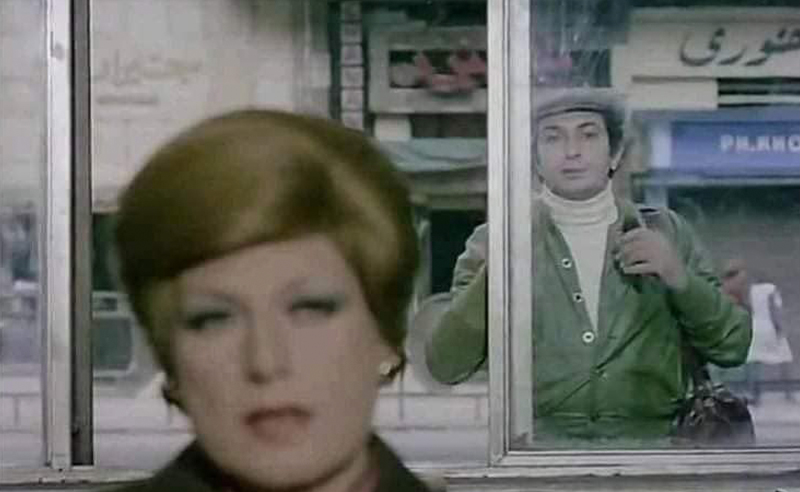

Kharag Wa Lam Ya’ud, 1984

Kharag Wa Lam Ya’ud, 1984

The defining characteristic of this movement was the emphasis on shooting at on-site locations rather than adhering to studio-based methodology. Critic and writer Ahmed Shawky recounts Mohamed Khan's insistence on filming in a restaurant near Cinema Metro in downtown Cairo during the shooting of ‘Darbet Shams’, even when producer Nour El Sherif suggested recreating the entire location within a studio. This illustrated Khan's - and his generation's - uncompromising approach to authentic storytelling and dedication to capturing the heartbeat and chaotic muse of Cairo during that era.

Khan stands as a pivotal figure in the neorealism cinema movement, recognised as one of its foremost pioneers alongside Atef Al-Tayeb, Dawood Abd El-Sayed and Khairy Beshara, with additional contributions from their contemporaries. This new wave of directors were not only representative of their cinematic influences, but also to a generation that faced unparalleled disillusionment due to the repercussions of the 1967 defeat and the six years that followed. These years shattered their dreams of Nasser’s failed nationalism and brought drastic societal and economic changes under President Anwar El Sadat, who reshaped the economic, social and cultural landscape. This generation witnessed their victory slipping away with the advent of American capitalism and globalisation.

Much like the Italian neorealism movement that emerged after World War II, led by directors such as Roberto Rossellini, Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni, these significant political events largely - and perhaps exclusively - fuelled both movements, which occurred 40 years apart. Both movements ventured into the streets to create films that resonated with the people, depicting their everyday struggles and documenting life as it was. They told the stories of the marginalized and the defeated, as well as those who adapted to and benefited from the socio-political changes.

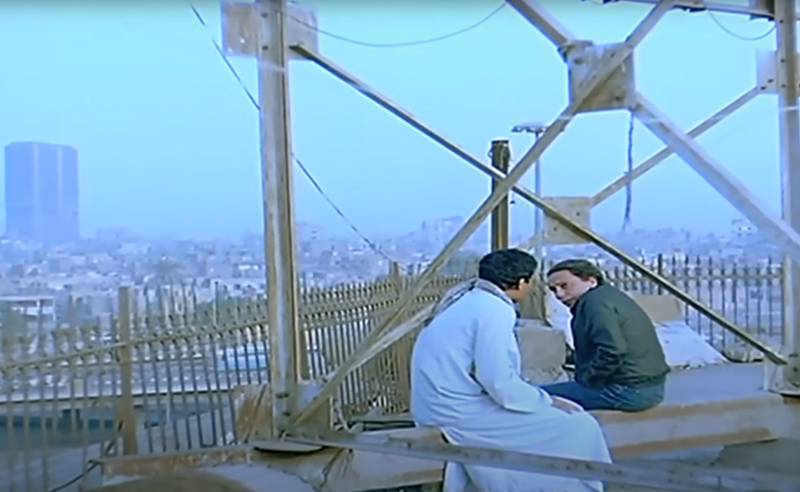

Darbet Shams, 1978

Darbet Shams, 1978

Crucially, this wave broke Egyptian cultural taboos involving subjects like sex, religion and politics - topics previously avoided or rarely discussed in Egyptian cinema. Critic Ahmed Shawky’s book on this neorealist movement, ‘Forbidden on Screen: The Taboo in the Cinema of the Eighties Generation’, delves into this subject at length, contending that these films were not only remarkable for their stylistic and thematic richness but also served as a social and political critique of the era. “The society here refers to the world at the end of the 1970s, the period following the October victory and the peace treaty. It was an era when the shock of a youth that had lived the national dream and fought for its goals coincided with their realization that their victory was the first nail in its coffin, amid a fast and strange social and economic movement that changed all the concepts and laws governing human relationships,” Shawky remarks on Atef El-Tayeb’s ‘Sawaq Al-Autobees’.

The concept of "place" was ambiguous and rather intangible in Egyptian cinema before the emergence of that movement, as filmmakers previously relied on studio sets without considering the importance of ‘place’. As a result, films were set in places that had no significance in shaping the story, making the characters appear as if they existed in an unrealistic, self-contained world. What this generation brought to Egyptian cinema, besides venturing into the streets and challenging traditional cinematic themes and subject matters, was giving the ‘place’ its due as an essential element in story development and, at times, even its protagonist. One can easily visualize Cairo by watching films such as ‘Al-Hareef’, ‘Darbet Shams’, ‘Love on the Pyramid Hill’, and ‘The Bus Driver’, among other films from the neorealism movement.

Al-Hareef, 1983

Al-Hareef, 1983

In a candid reflection on the cinematic movements of the past, critic Ahmed Shawky challenges the long-standing categorization of certain films as “realist.” “I don’t think describing this type of cinema as ‘realist’ is entirely accurate,” Shawky explains. “It was more of a term used as an umbrella to group together different trends in filmmaking. If we think about it, films by Khairy Beshara are different from those by Mohamed Khan, which are also distinct from Atef El-Tayeb’s films. There was an attempt to bring this generation under one critical framework.”

Shawky highlights how this nuanced wave of filmmaking created a fertile ground for collaboration between visionary directors and A-list actors - a synergy he argues is now missing. “If there's truly something missing in cinema today, it’s the relationship between major stars and directors who make alternative and experimental cinema,” he tells CairoScene.

Unlike today’s emphasis on box office dominance, directors like Beshara, Khan, and El-Tayeb prioritized storytelling and artistic impact over commercial success. “Their films weren’t the ones pulling in huge crowds or dominating the box office. Instead, they were important films - ones where actors could deliver strong performances, gain recognition at festivals, win awards and build an artistic legacy, regardless of mainstream success,” Ahmed Shawky, President of the International Film Critics Federation.

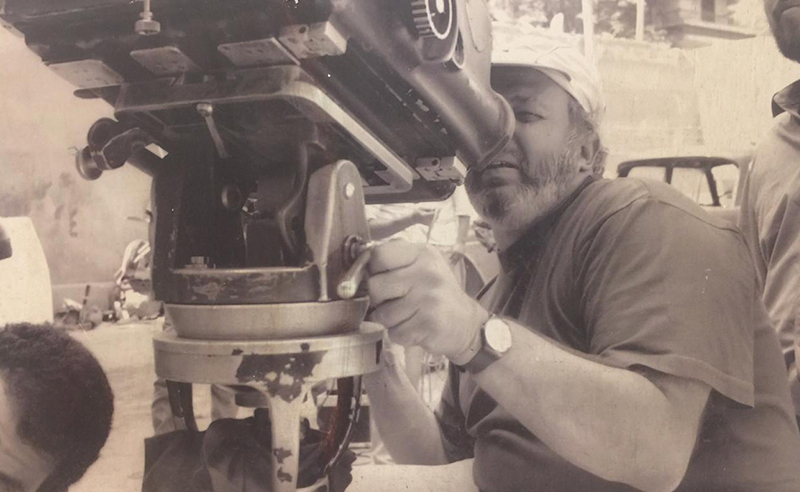

Mohamed Khan, Filmmaker

Mohamed Khan, Filmmaker

His critique underscores a broader concern: the diminishing role of star power in bridging mainstream and experimental cinema - a dynamic that once defined an era of rich, culturally significant storytelling in Egyptian film.

We can look back on this era to gain a deeper understanding of Cairo and Egypt during this transformative time, seeing how the significance of ‘place’ was brought to life through genuine storytelling. This generation of filmmakers shifted the narrative by elevating real locations to more than just backdrops; they became vital, dynamic elements of storytelling, shaping and influencing the characters and their journeys. The streets, neighbourhoods and landmarks of Cairo emerged as silent protagonists. These films portrayed the everyday of Cairene life, capturing its streets, rooftops and public spaces. They reflected the city’s character and the realities of those who lived there.

Sawaq Al-Autobees, 1982

Sawaq Al-Autobees, 1982

These films also documented the landscape and topography of Cairo and other locations during that period, as well as the political, cultural, and social conditions of the people. The metro in ‘Darbet El Shams’, the scene of Adel Imam standing under a massive Toshiba billboard, and the rooftop apartment where Faris lived in ‘Al-Hareef’ overlooking Tahrir Square, along with workplaces, Cairo’s streets, public squares, cafes, and bars - these scenes provided an unprecedented and vivid portrayal of Cairo.

Today, this grounded storytelling approach is less common, with many contemporary films adopting different styles or narratives that explore different subject matters. As a result, the Cairo that once mirrored its people’s lives has receded from the cinematic forefront. This shift highlights how neorealism effectively documented its era, but as Egyptian cinema has evolved alongside broader cultural and societal changes, the city’s role in the story has transformed, no longer occupying the central place it once did.

- Previous Article hhhhhhhhhhhhh

- Next Article Dissecting the Layers of Cairo With Moroccan Stylist Nathalie Sicart

Related Articles

Trending This Week

SceneNow TV

Events Calendar