Egypt’s First Soda Brand is Making a Comeback… & Rightfully So

Spathis’ enduring legacy can truly never wither.

The world’s gaze is shifting, and it’s doing so at a rapid pace. Who can we trust when the brand’s we’ve blindly consumed have been leading us astray, funding the same people tearing children’s worlds apart with their bare hands? How can one guarantee that their consumption doesn't directly help fuel a genocidal mission? The answer to most people remained simple: boycott and replace. Infographic carousels from a myriad of different countries began to circulate soon after ‘support statements and donations’ were made; ones that delineated local alternatives to international products. One product in particular has been circulating heavier than most - Egypt’s first soda brand, Spiro Spathis.

Established in 1920 by Greek entrepreneur Spiro Spathis, the localised soda brand was built on zesty principles - a lemonade-flavoured sparkling drink. Yet, a certain question constantly bubbles beneath the surface when Spathis heritage is addressed; why would a Greek man actualise his soda-flavoured dreams in a country that’s not his own? Well, Spathis' move to Egypt was not by choice; it was rooted in colonial displacement and a period marked by British rule that dominantly shaped the Mediterranean from 1882 until 1956. Egypt became his adopted home, and his business served as a platform for him to introduce fresh and innovative beverages to its F&B market.

Established in 1920 by Greek entrepreneur Spiro Spathis, the localised soda brand was built on zesty principles - a lemonade-flavoured sparkling drink. Yet, a certain question constantly bubbles beneath the surface when Spathis heritage is addressed; why would a Greek man actualise his soda-flavoured dreams in a country that’s not his own? Well, Spathis' move to Egypt was not by choice; it was rooted in colonial displacement and a period marked by British rule that dominantly shaped the Mediterranean from 1882 until 1956. Egypt became his adopted home, and his business served as a platform for him to introduce fresh and innovative beverages to its F&B market.

In the years following the opening of a Spiro Spathis factory, the company's portfolio expanded as rapidly as its local popularity. In 1921, an Apple Cider flavour made its debut, followed by tonic water and a bottle rebrand in 1925. The year 1935 saw the introduction of Ginger Ale, Lime Juice & Soda, Grenadine, and Grapefruit flavours and in 1941, the brand's local success was honoured with a King Farouk I medal. Despite Spathis’ passing in 1950, his daughter Aftakhia remained unwaveringly committed to preserving his vision; a mission that lasted until the late 90s. In 1998, the company and its trademark found new ownership with MYMCO for food and beverages (formerly known as SAPSA). MYMCO swiftly began expanding Spiro Spathis’ product line - a facelift that still ensured the brand was recognisable to the public eye. Today, with a 100-year legacy beneath its steel bottle cap, Spathis is re-gaining notoriety and basking in its well-deserved spotlight.

In the years following the opening of a Spiro Spathis factory, the company's portfolio expanded as rapidly as its local popularity. In 1921, an Apple Cider flavour made its debut, followed by tonic water and a bottle rebrand in 1925. The year 1935 saw the introduction of Ginger Ale, Lime Juice & Soda, Grenadine, and Grapefruit flavours and in 1941, the brand's local success was honoured with a King Farouk I medal. Despite Spathis’ passing in 1950, his daughter Aftakhia remained unwaveringly committed to preserving his vision; a mission that lasted until the late 90s. In 1998, the company and its trademark found new ownership with MYMCO for food and beverages (formerly known as SAPSA). MYMCO swiftly began expanding Spiro Spathis’ product line - a facelift that still ensured the brand was recognisable to the public eye. Today, with a 100-year legacy beneath its steel bottle cap, Spathis is re-gaining notoriety and basking in its well-deserved spotlight.

Spathis rose to pop culture ranks after multiple cinematic appearances. While the drink was never the protagonist, its presence always grounded films within their greater historical context. Two films in particular heavily featured the drink, enabling its inextricable ties to Egyptian culture to permeate screens across the country.

Spathis rose to pop culture ranks after multiple cinematic appearances. While the drink was never the protagonist, its presence always grounded films within their greater historical context. Two films in particular heavily featured the drink, enabling its inextricable ties to Egyptian culture to permeate screens across the country.

The drink's socio-cultural relevance is vividly portrayed in the 1958 classic 'Bab El-Hadid' (Cairo Station). Hanouma, powerfully portrayed by Egypt's Hind Rostom, embodied the role of a soda seller, a Spathis soda seller to be more specific. Scenes featuring the actress holding the rebranded bottle reinforce its strong cultural ties and its seamless integration into daily activities.

The drink's socio-cultural relevance is vividly portrayed in the 1958 classic 'Bab El-Hadid' (Cairo Station). Hanouma, powerfully portrayed by Egypt's Hind Rostom, embodied the role of a soda seller, a Spathis soda seller to be more specific. Scenes featuring the actress holding the rebranded bottle reinforce its strong cultural ties and its seamless integration into daily activities.

A more recent satirisation of Spathis' prominence can be witnessed in the 2010 comedy 'Samir w Shaheer w Baheer.' In this film, the protagonists find themselves transported back in time, landing in the 1970s. As they struggle to navigate an era vastly different from their own, they seek refreshment at a local 'koshk' (kiosk). Faced with the realisation that they are in a world without cell service, 'Samir w Shaheer w Baheer' attempt to order a drink, asking the mullet-sporting man behind the window if they have Fayrouz. Their query is met with silence. "Not even a Pineapple Fayrouz?" they inquire. Still, only crickets. "What do you have?" they persist. "We have Spathis," the cashier responds enthusiastically.

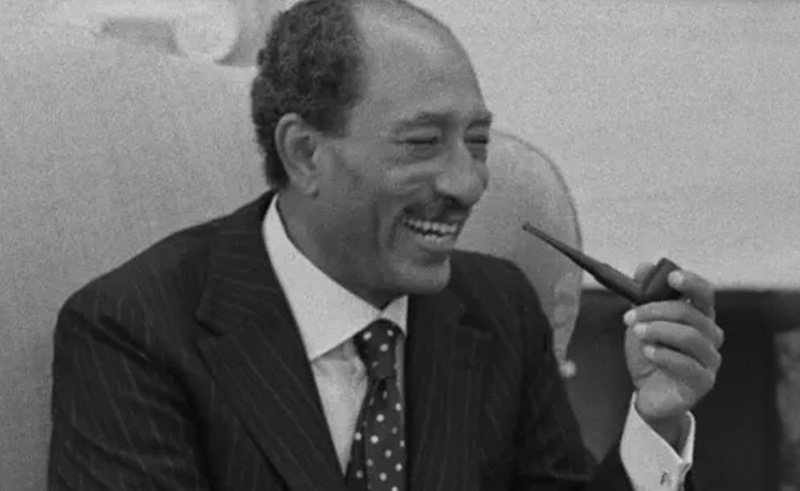

In 1975, Egypt's third president, Anwar Sadat, implemented the Infitah [Open Door Policy], which was a pivotal economic policy that sought to rejuvenate the country's stagnant economy and reduce its dependency on socialism. One of the key elements of this policy was the embrace of Western consumables. Sadat aimed to bolster the economy by attracting foreign investments and integrating the nation into the global economy. As a result, Western goods and products flooded into the Egyptian market. Previously unavailable or limited luxury items became more accessible, reflecting a growing consumer culture in the country. While this policy offered Egyptians access to a wider range of products and a taste of international trends, it also led to increased dependency on foreign goods and a decline in domestic industries.

In 1975, Egypt's third president, Anwar Sadat, implemented the Infitah [Open Door Policy], which was a pivotal economic policy that sought to rejuvenate the country's stagnant economy and reduce its dependency on socialism. One of the key elements of this policy was the embrace of Western consumables. Sadat aimed to bolster the economy by attracting foreign investments and integrating the nation into the global economy. As a result, Western goods and products flooded into the Egyptian market. Previously unavailable or limited luxury items became more accessible, reflecting a growing consumer culture in the country. While this policy offered Egyptians access to a wider range of products and a taste of international trends, it also led to increased dependency on foreign goods and a decline in domestic industries.

Over the last fifty years, Spiro Spathis started falling off the shelves in favour of imported soda brands, and the newer generations of consumers were encouraged to believe that products brought in from the West were automatically better.

Over the last fifty years, Spiro Spathis started falling off the shelves in favour of imported soda brands, and the newer generations of consumers were encouraged to believe that products brought in from the West were automatically better.

The truth is, Spathis has remained a cultural staple. Ironically, its resurgence is a response to the same violence that brought it to life. Spathis wouldn't have become an integral part of Egyptian culture without the founder's displacement. Today, as the world becomes more aware of whose agendas are closely aligned with those of malevolent oppressors, people return to their roots and, in the end, shun those who have stood on the wrong side of history.

The truth is, Spathis has remained a cultural staple. Ironically, its resurgence is a response to the same violence that brought it to life. Spathis wouldn't have become an integral part of Egyptian culture without the founder's displacement. Today, as the world becomes more aware of whose agendas are closely aligned with those of malevolent oppressors, people return to their roots and, in the end, shun those who have stood on the wrong side of history.

- Previous Article سندباد الورد أضحي سلطاناً: مراجعة لألبوم شب جديد والناظر 'سلطان'

- Next Article Egyptian Embassies Around the World

Related Articles

Trending This Week

-

Nov 04,2024

SceneNow TV

Events Calendar